The problem(s) with design tokens

As design systems evolve, managing tokens across tools, code, and documentation has become routine. However, relying solely on tokens as the ultimate source of truth introduces unnecessary complexity and constraints. This post highlights common limitations of design tokens and highlights the importance of modeling design contexts.

While the early days of design systems were mostly about becoming familiar with the concepts of patterns and components, the last couple of years focused heavily on adopting design tokens as the core mechanism to distribute design decisions.

Synchronizing thousands of tokens across various platforms, tools, codebases, and even documentation is now part of the daily routine for any mature design systems project.

Design tokens, everywhere!

This surge in complexity has led to many feeling overwhelmed, especially those who are less technically inclined. If this is your case, don’t worry, you have thousands of Medium articles to get started on the topic. And dozens of specialised courses to get you up to speed.

Meanwhile, innovation doesn’t stop. Design token management has been incorporated in the offerings of established companies such as Supernova and an endless number of specialised products, such as Use Design Tokens, Arcade, and Knapsack are emerging to support the growing ecosystem.

And what started simply as a design tokens plugin for Figma is promising to revolutionize design systems. Although it’s taking months to release their Token Studio product.

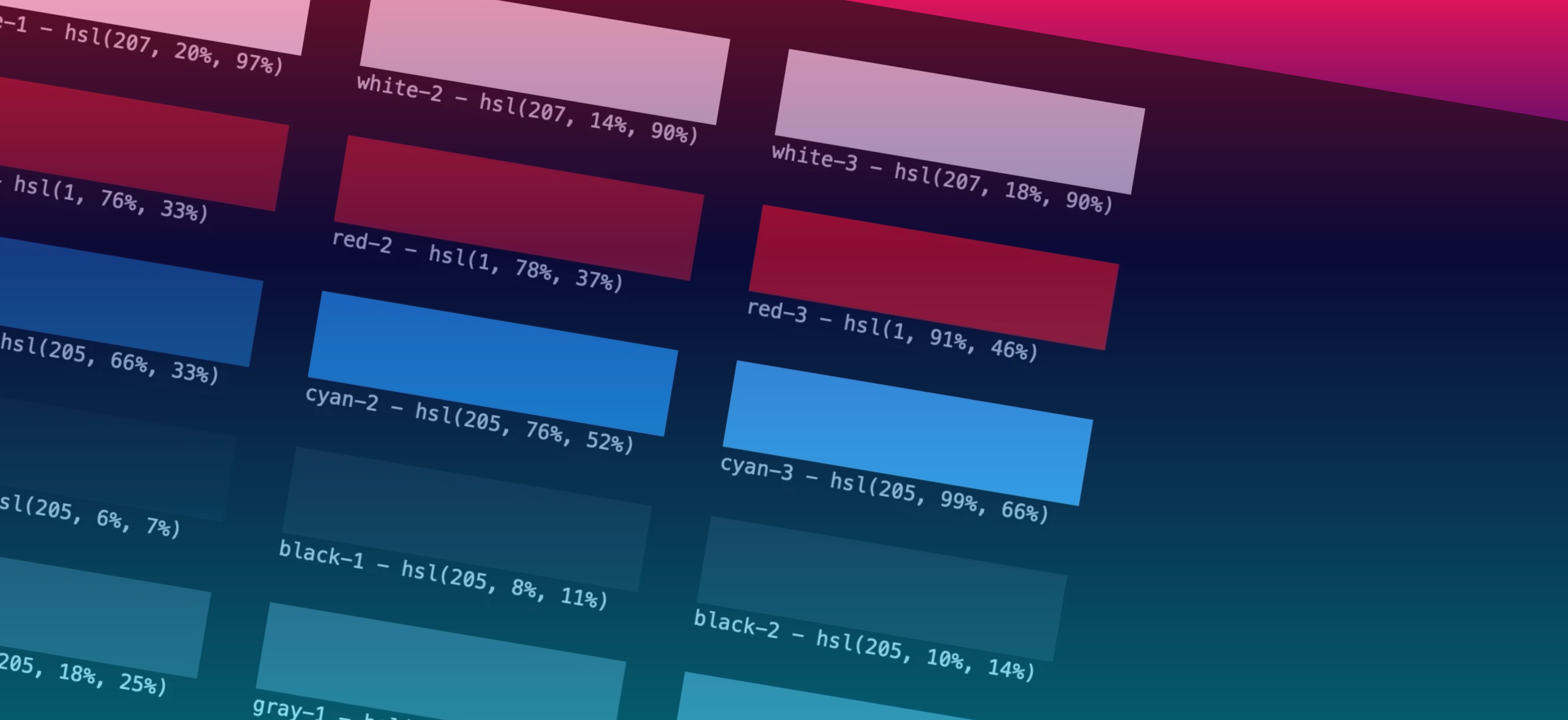

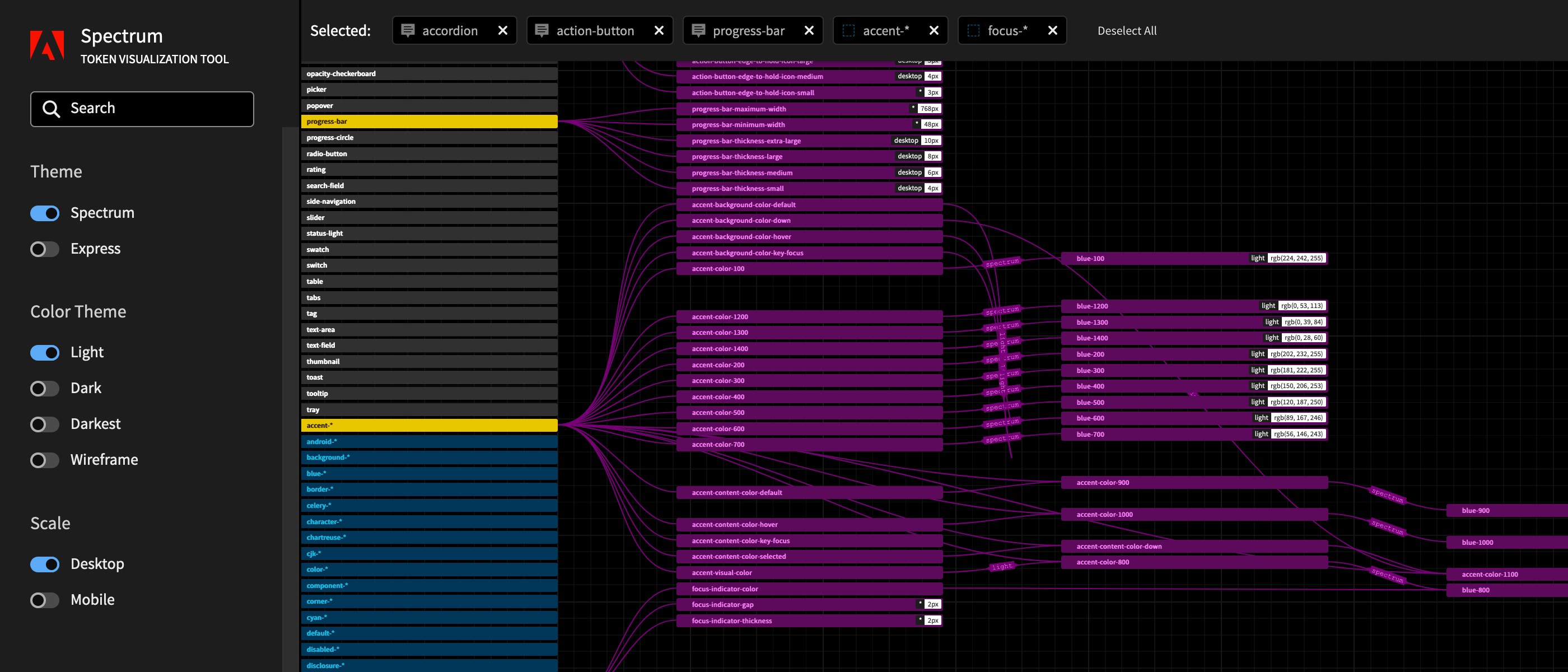

A quick look at the design systems of big companies shows how much investment is made in token management by those with the budget to develop their own pipelines. Take Adobe’s Spectrum or IBM’s Carbon for example, where token types, schemas, and taxonomies are all modeled as code. With this in place, they have full control over source of truth (example) and transformations (example). Moreover, they can generate documentation (example), track relationships between tokens, and develop bespoke visualizations (example).

Design tokens as code, typings, and documentation have also become the daily focus of engineers and an essential concern of component libraries. The topic is even starting to surface on the architects’ radars 🧐. Here’s a recent post on Design Token-Based UI Architecture by Andreas Kutschmann to illustrate the point.

Design tokens are design decisions as data and serve as a single source of truth for design and engineering.

That’s the current statement — a good enough summary for those getting started on the topic. But it also reflects how early we are in this journey and how much work lies ahead.

Design token limitations

While tokens are a powerful model for representing and distributing design decision values (like colors, sizes, and typefaces), treating them as the source of truth is coupling our tools with the wrong abstraction.

Tokens map the values produced by design decisions, in specific contexts, to naming conventions. These mappings are usually closely tied to particular use cases and structured around technical constraints and concerns. Token lists tend to be flat, with the token name as the defining element. From my experience, most design decisions that lead to new tokens are often riddled with complexities, process hurdles, and technical chores. Ultimately, these decisions are shaped by technical factors, like the ergonomics of CSS variables and the limitations of design tools — yes, Figma, I’m looking at you 😉.

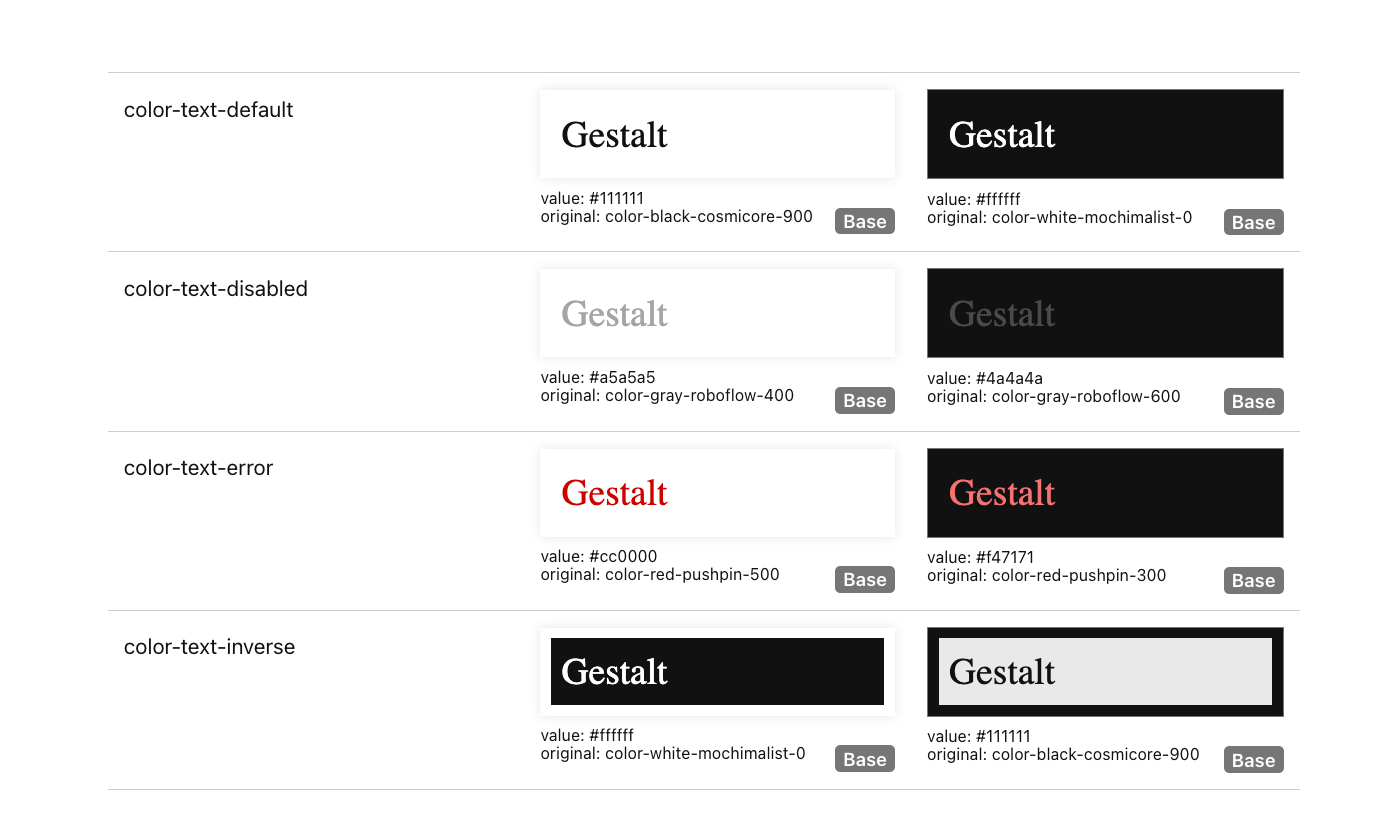

In this example from Gitlab’s color tokens, the color-text-inverse token results from a decision to render light text on a dark surface when in light mode, and vice-versa. As a result, this token is tightly bound to the background-color context its meant to be used in and can not be used over other backgrounds.

One of the reasons we have so many tokens in our systems is that we are forced to duplicate decisions and values across contexts. This happens because our tools — guess who am I thinking of — lack both:

- a way to explicitly define (and infer) context.

- a way to resolve default values;

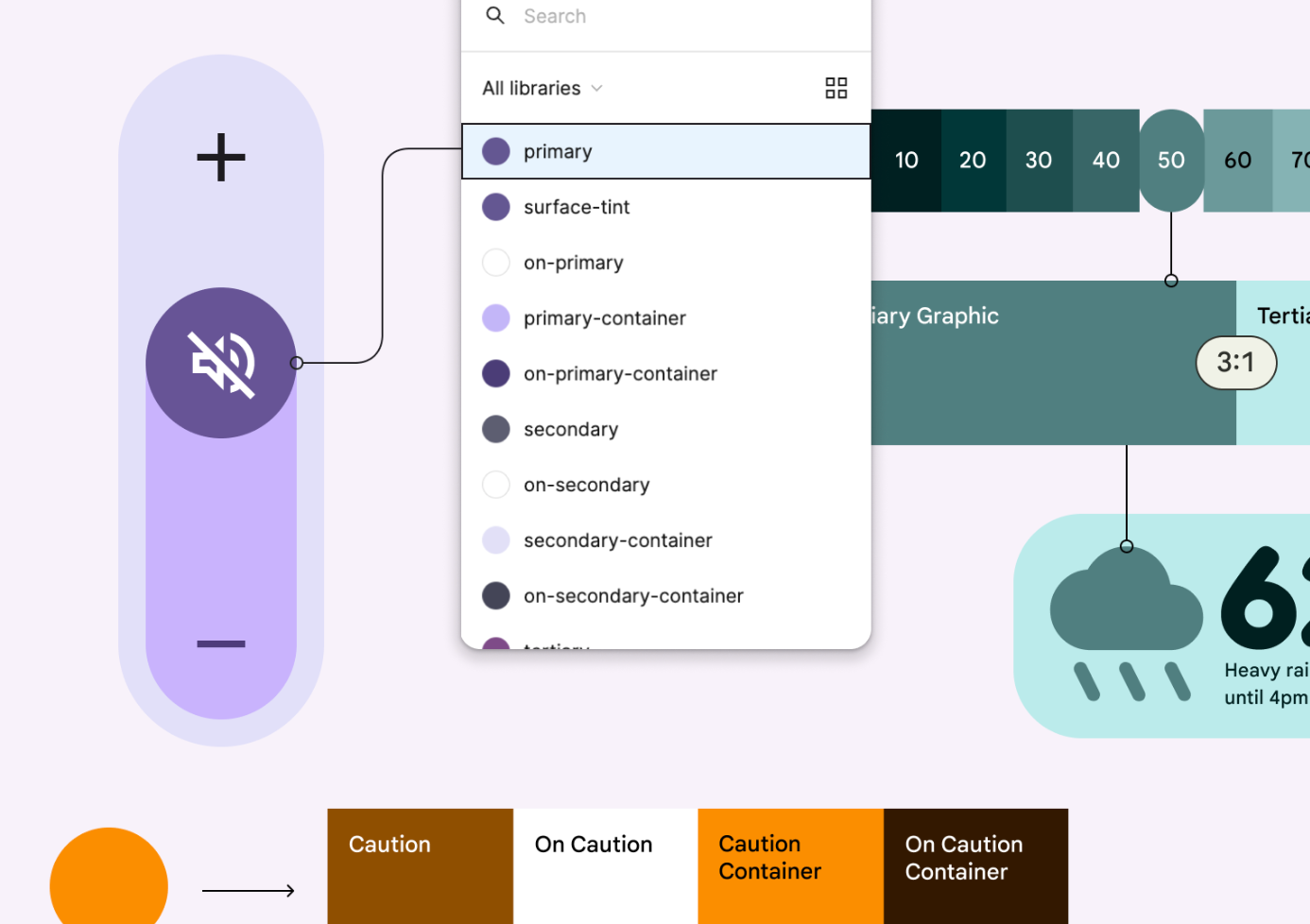

The following example of Google’s Material UI, even if tremendously well executed, illustrates this well.

The ...-on-primary tokens should only be used inside a certain container but are available in wider scopes. This leakage of the design context into the options and values layer has a few nasty consequences:

- confuses designers and developers

- allows for errors to be made

- makes the system less flexible

- makes the system harder to learn

In the case of IBM’s Carbon, the team has gone the distance in modeling layer contexts into their token system.

A field is considered a layer on top of the background it is placed on, for example a field placed on a $layer-02 background will use $field-03. Border tokens however, pair with its same number, for example $field-03 pairs with…

What? 😫?

IBM’s token system is very effective at implementing their sophisticated layering system. It is also quite rigid and probably hard to evolve later. It is also difficult to understand. And as the above quote illustrates, also difficult to explain (example).

When all you have is a hammer…

…everything looks like a nail.

Not the first time I drop this quote here 😅, but our industry does it as often as the opportunities present themselves: we reframe our challenges around the tools, especially the latest shinny toy. And in the process, we lose sight of what we were originally trying to achieve.

The modern design system uses tokens to distribute centrally managed design decisions and it faciliates iterating on brand and visual language. In most of the cases it support light/dark mode context but some are also dealing with multiple brands and identities at the same time. With some effort and crafty engineering, many are building token pipelines with integrations, transformations, and automatic docs generation.

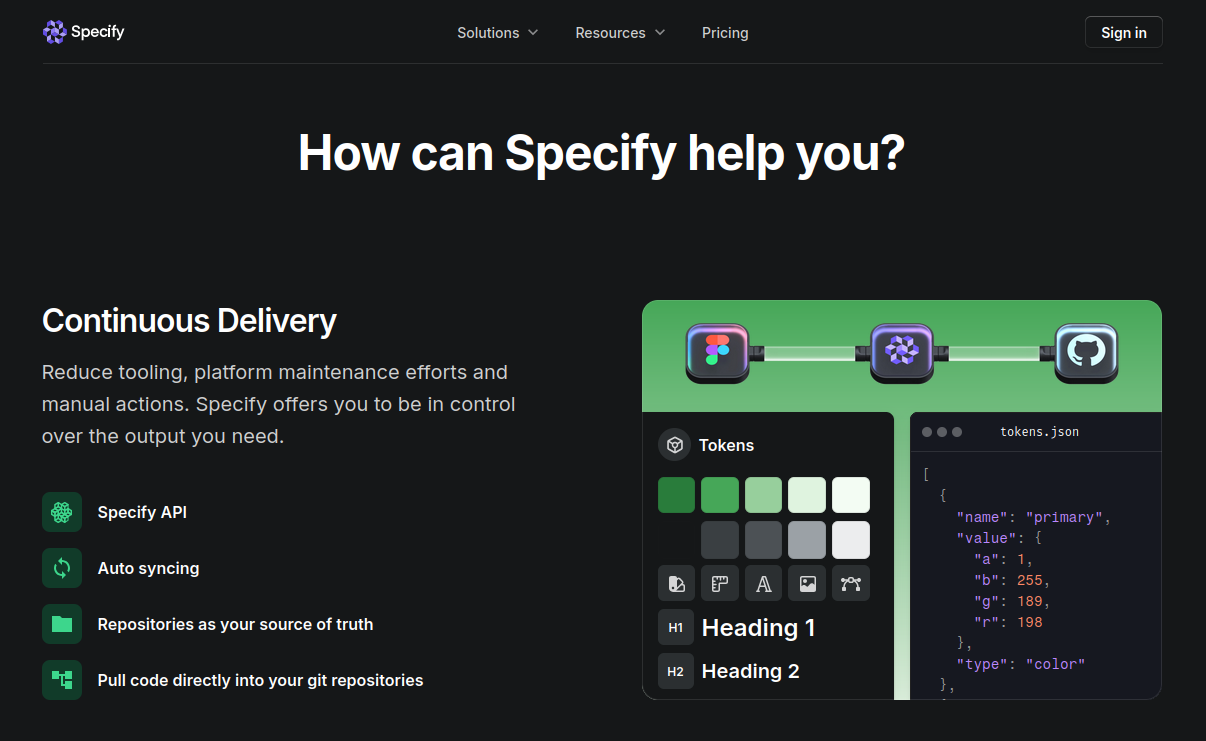

From all the contenders in the design token SASS space, I was particularly excited about Specify and their promise to deliver a tool-agnostic platform for collecting, storing and distributing design data. But their journey was a short one 😢.

I am sad to see them go, maybe they could’ve taken it from there as they appeared to already have a good deal of clients.

I truly believe we became one of the best platforms out there, helping many teams every day. But in the end, it wasn’t enough to create a sustainable business. Despite our best efforts, we couldn’t find our product-market fit.

As far as I understand, their decision data central model was based on design tokens. I know from experience that design tokens are only fit to represent design decision in limited use cases, modeled around specific design tools, CSS, and other implementation details.

And above all, design tokens lack crucial information about the decisions: design context, application, guidelines, and so on.

Is it possible that the market potential for a design token pipeline as service is actually not enough to create a sustainable business? Asking for a friend 😉

My gut feeling? As long as we continue to treat tokens as the holy grail of design data, we are destined to run into the same challenges daily. And to chose between:

- settle for under-designing 😞

- embrace the over-engineering 😫

- design and code outside of the systems 😱

There is no winning here, only underwhelming options.

So, what’s next?

While this post focuses mainly on identifying the limitations of design tokens, I intend to come back to this topic soon, exploring ways to break out of this mold and model design decisions with context at its core.

This will require a thorough discovery phase of design contexts. I look forward to uncovering how different systems are evolving beyond tokens, finding inspiration in those reimagining and remodeling their decision data.

Meanwhile, I am also engaging in hands on prototyping: Designer Decisions is a project I recently started with some friends. Our first goal is to provide a comprehensive set of documentation primitives for contextual design decisions. Token agnostic, of course.

Previous post Writing doesn’t have to be hard