Building a backlog from a messy prototype

Building a backlog from a messy prototype can be challenging, but it’s essential to change gears and depart from the prototyping mindset. Here are some strategies to deal with cognitive overload and to quickly start breaking down the chaos into meaningful, actionable, and purposeful tasks.

Last night was tough in Champions League football, with my team Benfica playing with Barcelona. They were 4-2 up with 20 minutes to go, but things got complicated 😅.

Yesterday was also a great day at the office, though. We made significant progress on building a backlog for the Designer Decisions project, entering a new stage focused on execution.

Prototypes are messy

After working on a proof of concept back in the summer – a POC that totally missed the mark, unfortunately – I stumbled upon a couple of breakthroughs in November. With help from some friends, we developed a prototype in less than a month and it validated our initial assumptions while mitigating the scariest risks:

If we can do this 💪 we can also build that!

Due to the nature of the project, this optimist sprint also resulted in an overwhelming amount of code and documentation (automating documentation is a significant aspect of the project 😅). This led to a lot of mental strain, and a constant need to dribble around unfinished tasks, fundamental doubts, and occasional blockers.

To manage the overwhelming vortex of information, during the prototyping phase, we took notes with discipline, generating numerous TODO files and inline comments. We paused frequently to (re)analyze various problems. We had to rewind the tape and refactor many aspects, which left even more loose ends to address.

Despite the effort, by the time we called it DONE – oh! the irony – the prototype, the docs, and the code were full of WIP and TODO comments. And, in some cases:

TBD, Not enough information

As soon as we published the first version of the docs and the first packages on npm, we took a break to automate everything. We terraformed domains, certificates, distributions, the works. Then, we set up GitHub Actions to deploy the docs automatically 😋. Satisfying!

When it was time to return to the code, though, I started feeling a bit anxious. Where did we leave off? What was the next step?

So many questions 😵! And looking at the notes wasn’t helping.

Planning a first release

We have big plans. Wild dreams. But now is the time to build a backlog, start sequencing work, and get (cool 😎) things done.

We completely set aside the question of “what’s the next step” for a while – three days, to be exact – and compiled all the notes into a couple of files. The first goal was to determine what should be in the next release. Quickly, and roughly.

We are aiming for a v0.1.0 that implements a couple of use cases end-to-end. Since Designer Decisions is essentially a model with a bunch of APIs around it, we need to be confident that we won’t introduce many breaking changes.

With that in mind, from these two files emerged a first cut:

- Must have - use cases are not complete without these tasks.

- Nice to have - tasks that will improve the experience but are not essential.

- Out of scope - not required for the release.

And let’s not forget the Big Dreams bucket. I like to keep all those ideas around, no matter how wild they might seem. I keep them neatly organized, but far away from my sight 😇. And when I stumble upon new ideas or breakthroughs, when I find myself daydreaming instead of working, I know exactly where to write them down. And more importantly, I can get back to work!

Backlogging provides clarity

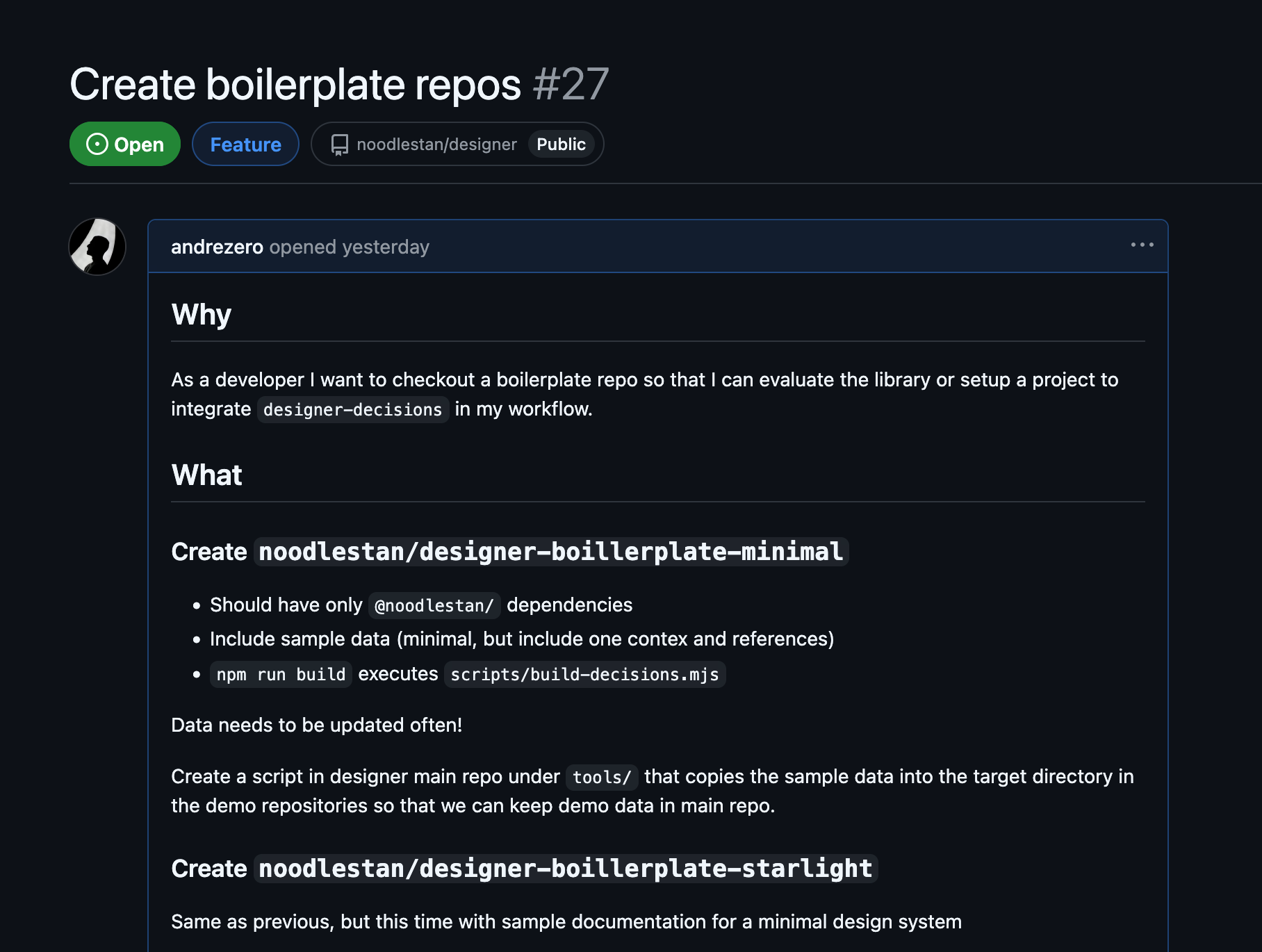

The next step was to break everything down into discrete tasks. We still need to answer the “What’s next?” question. Which requires prioritizing things, … which requires defining their value, and scope, and … Which requires knowing why we think the task is important in the first place 😀.

Since the project is being built in the open, we also want to leave a clear paper trail of decisions for future reference. And set an example for how to communicate around increments. We also believe that tickets with clear why – ideally, user stories – and just enough design, make it easier to sequence the work. We also believe that good tickets minimize chances of delays and rework.

I started by tackling the straightforward tasks to declutter the backlog and create some momentum. Indulging in the smaller tasks, creating well-structured tickets and watching the backlog grow 😍 brought some joy back to the game.

Also, while adding details to the first tickets, new dependencies were revealed. And occasionally, it provided hints on how to solve the harder problems.

This was like scoring a couple of goals in a row. ⚽ ⚽ Almost like when Benfica went 3-1 up just 20 minutes after kick-off.

After the first day, the cognitive pressure lifted. With less information cluttering my mind, I could now discuss the missing bits without confusing my interlocutors — or myself.

However, the anxiety around the same fundamental questions remained. The dependencies between tasks, especially within the main features we planned to implement next, were still unclear. Worse, some fundamental pieces of the puzzle, too risky to leave as “we’ll figure this out later”, were still refusing to fit together.

The only option left was to revisit the prototype, dig back into the code, and ask even more questions 🙄.

Hum… This 5AM commit is a bit weird.

Turns out that returning with a fresh perspective – now backed by a structured backlog – provided the headspace that had been missing for a while. The first surprise was to find that some of the disciplined notes were completely out of sync with the working code. A late night decision to “document this tomorrow morning” had been biasing some of the early conclusions.

At this point, I realized we had asked almost all the right questions, but had also stuck with some shortsighted, midnight-oil, 😴 tired solutions. After this breakthrough, it took less than a day to try out different approaches, directly in the code. Focused again on the APIs we want to deliver, unburdened by the prototype’s half-baked solutions, the missing “tickets” practically wrote themselves.

Thinking (too early) about time is a waste of time

When should we start a task? And how long will it take to complete it? These are crucial questions when planning increments. Answering them is key to many things, such as achieving flow, minimizing waste, forecasting delivery, and synchronizing dependencies. However, when building a backlog — or refining work, for that matter — you will move much faster if you don’t spend too much time debating timelines.

Why and Scope are the essence of a unit of work. When breaking down tasks and untangling dependencies, the only timing questions that matter are in the form:

Can we start this before we finish that?

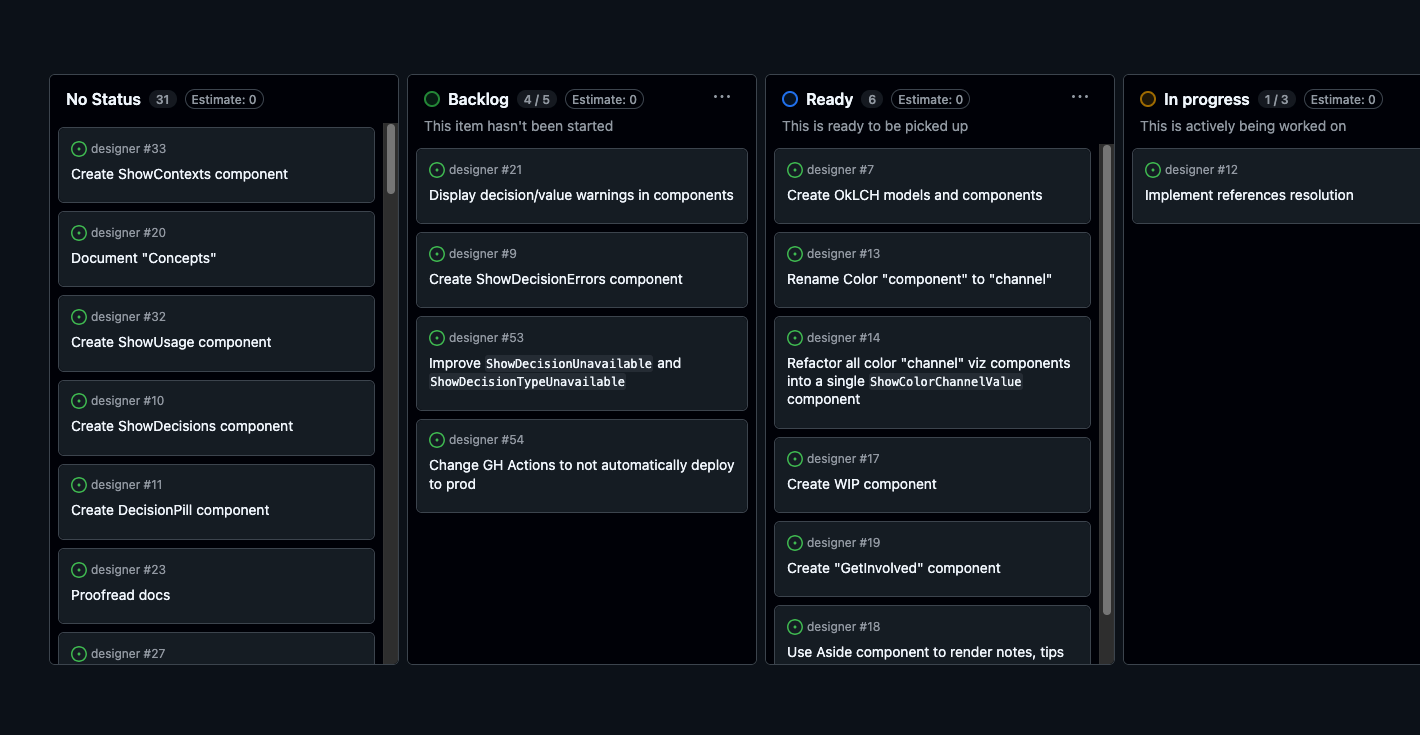

While building this backlog, we frequently changed the status of tasks between “ready,” “needs planning,” “out of scope for the release,” and back to “priority #1.” Sometimes, small adjustments to scope or breaking a task into smaller ones can radically affect when it’s optimal to sequence it.

So, if you’re unsure about priorities, struggling to decide if something is a “must-have” or a “nice-to-have,” it probably means it’s too early to ask that question. In such cases, toss a coin and move on. You will know that you have a better answer when when you see it.

What’s next?

Now is a great time to ask that question.

The backlog is all on Github. Sort of terrifying 😬 and exhilarating at the same time, to be honest. More importantly: now we can pick up tasks and flow. Personally, I find it reassuring to know “what’s next” any given morning, without having to wear the planning 🤔 hat before I finish my morning coffee.

We will continue reshuffling priorities as long as we need it, of course. And while we have a clear path to some destinations, we need to continue our research. The domain we are venturing into is not sufficiently modeled by any open source or commercial tool that we know of. We are very suspicious of this 😕.

Oh! And Benfica? ⚽ Lost 4:5. Missed a goal on 90’+4 minutes and Barça scored on the counter.

Previous post The problem(s) with design tokens

Next post What happened to contextual styling?